Diary of a Rambling Antiquarian

Friday, 13 December 2013

Ancient Lotus Pond

Every time I visit China, I try to go somewhere I have never been to before in search of historic inscriptions in the various scripts that I study. In January 2005 I went to look for Christian tombstones with Phags-pa inscriptions held at the Museum of Maritime History in Quanzhou, and in August 2011 I went to look for Buddhist texts engraved in six scripts on the Cloud Platform at Juyong Pass. This time in Beijing I only have two free days, and after yesterday's trip to the Tianning Pagoda, there is only today left, so wherever I go has to be within a day trip from Beijing. Luckily, the place that I have in mind is the city of Baoding 保定, just 90 miles south-west of Beijing, and only an hour and a half by train (or 45 minutes on the newly opened high speed bullet train line, but I prefer slow trains). I had planned to go there by train, but my old friend Mr Chen has very kindly offered to take me somewhere on an excursion today, so we are travelling to Baoding together by car.

Historically Baoding has acted as the southern gateway to the capital, and its current name, signifying "Defend the Great Capital, Pacify the Empire" (保衛大都,安定天下), was given to it in 1275 during the reign of Kublai Khan. It is strategically located south-east of the Zijing Pass (紫荊關) and the Daoma Pass (倒馬關), and thus guards against incursions across the Great Wall by the nomadic peoples of the north. However its strategic location also made it a prime target for invaders, and so when Genghis Khan broke through the Zijing Pass in the 7th month of the 1st year of the Zhining era (July/August 1213), during the Mongol-Jin war, the Jin city of Baozhou (as Baoding was then called) was under immediate threat. A few months later Genghis Khan's sons led a force south along the Taihang Mountains, and almost exactly 800 years ago, during the 12th month of the 1st year of the Zhenyou era (January/February 1214), the Mongols attacked and destroyed the city of Baozhou, massacring its inhabitants, numbering more than 90,000 households.

Map of Beijing and Baoding (from Google Maps)

{©2013 Google}

Mr Chen picked me up at my hotel at 8:00, and after spending an hour stuck in the traffic trying to get out of Beijing, taking a convoluted detour because the highway to Baoding was closed half way there, and an hour in the traffic trying to get into Baoding, we arrive at about 11:30 at the Ancient Lotus Pond (Gu Lianhua Chi 古蓮花池) in the centre of Baoding. I cannot say that lotuses interest me particularly, and in winter they are not to be seen anyway, but I am here on a pilgrimage, because Baoding's Ancient Lotus Pond is an unlikely Mecca for Tangutologists.

The Ancient Lotus Pond in Baoding in winter

After the Mongols had laid waste the city of Baozhou it lay desolate and abandoned for nearly fifteen years, until Genghis Khan appointed Zhang Rou 張柔 (1190–1268), a military official under the Jin who had surrendered to the Mongols in 1218, as military governor of the Baozhou region. In 1227 Zhang Rou moved into the empty ruins of the city, and he started to rebuild and repopulate it. As part of his scheme of civic reconstruction he had a garden created for use as the private residence of his subordinate general, Qiao Weizhong 喬維忠. This Garden of Snow Fragrance (Xuexiang Yuan 雪香園) was renowned for its lotus pond, and is now called the Ancient Lotus Pond. Having parked the car around the corner, we find the entrance to the Ancient Lotus Pond (opposite Baoding Cathedral), buy our tickets, and escape the noise and madding crowds of the modern city. It is hard to imagine the carnage that took place here 800 years ago.

Entrance ticket (credit card sized) for the Ancient Lotus Pond

Courtyard of Steles

Immediately to our left, before we even reach sight of the famous lotus pond, we pass a courtyard, and through its entranceway we spy a pair of dark, mushroom-shaped pillars. These are surely the objects of our devotion.

Courtyard of steles at the Ancient Lotus Pond

宸翰院

Running around the inside of the courtyard is an enclosed corridor sheltering twenty-one stone tablets, steles, and pillars of various shapes and sizes, dating to the Yuan (1271–1368), Ming (1368–1644), Qing (1644–1911) and Republican (1911–1949) periods, some commemorating the renovation of the pond, others relating to the presence in the garden of an Academy of Classical Learning during the Qing dynasty.

| Admonishing Government Stele Ming, Jiajing 43 (1564) |

| 《政訓碑》 |

|

| {BabelStone CC BY-SA 3.0} |

| The stele is engraved with a poetic admonishment of government written by the Investigating Censor Xu Xiang 徐驤 when he inspected Baoding in 1564. |

| Lotus Pond Stele Qing, Kangxi 49 (1710) |

| 《蓮花池碑記》 |

|

| {BabelStone CC BY-SA 3.0} |

| The stele commemorates the renovation of the Lotus Pond by Li Shenwen 李紳文 (d. 1712) in 1710. |

| Lotus Pond Academy Stele Qing, Yongzheng 12 (1734) |

| 《蓮花池書院記》 |

|

| {BabelStone CC BY-SA 3.0} |

| The stele commemorates the establishment of an Academy of Ancient Learning in the grounds of the Lotus Pond garden in 1734. |

| Renovation of the Lotus Pond Channels Stele Qing, Qianlong 16 (1751) |

| 《重修蓮花池東西二渠記》 |

|

| {BabelStone CC BY-SA 3.0} |

| The stele commemorates the renovation of the east and west channels to the Lotus Pond in 1751. |

| Jiaqing Emperor's Fang Shouchou Poem Stele Qing, Jiaqing 16 (1811) |

| 《嘉慶賜直隸布政使方受疇詩碑》 |

|

| {BabelStone CC BY-SA 3.0} |

| The stele is engraved with a poem written by and in the calligraphy of the Jiaqing Emperor, commending the Provincial Administration Commissioner, Fang Shouchou 方受疇 (d. 1822). |

Tangut Dharani Pillars

As interesting as these steles are, they are not why we are here, and it is the two unusual, mushroom-shaped octagonal pillars that draw our attention. It is immediately obvious that these two pillars are not like the other steles in the courtyard, and when we get within touching distance we can see that they are not engraved with Chinese characters, but are covered in Tangut writing. For these are the famous Tangut Dharani Pillars of Baoding. They were discovered in 1962 on the site of a Buddhist temple in the village of Hanzhuang 韓莊 in the northern suburbs of Baoding, and were subsequently moved to the Ancient Lotus Pond (about three miles south of Hanzhuang), where they have remained ever since.

| Two Tangut Dharani Pillars |

|

| {BabelStone CC BY-SA 3.0} |

According to the Tangut inscriptions on the pillars (and a single line of Chinese text shown below), the two pillars were erected during the middle of the Ming dynasty, in the 15th year of the Hongzhi era (1502) by Trashi Rinchen བཀྲ་ཤིས་རིན་ཅན་, the Tibetan abbot of the Temple for Promoting Goodness (Xingshan Temple 興善寺), in memory of two monks who had recently died. The octagonal pillars are engraved with the Tangut transcription of the Dharani-Sutra of the Victorious Buddha-Crown (Chinese: 佛頂尊勝陀羅尼經; Sanskrit: Uṣṇīṣa-vijaya-dhāraṇī-sūtra), a text recited to facilitate the transmigration of the souls of the dead. This is also one of the two dharani-sutras engraved in Tangut and five other scripts on the Yuan dynasty Cloud Platform at the Juyong Pass, north-west of Beijing. But these pillars were erected over 150 years after the Tangut dharani-sutras were engraved on the Cloud Platform in 1345, and are by far the latest known surviving examples of the native use of the Tangut script.

Me and Mr Chen in front of the Tangut dharani pillars

The pillars are protected from visitors by a brightly painted wooden fence with swastika designs, and at first I am afraid that I will be unable to see the Tangut text on the far sides of the pillars, but we quickly find a small gate into the enclosed corridor, and as it is not padlocked and there is no sign forbidding entry we boldly (and probably incorrectly) assume that we are allowed inside the corridor of steles. The light is perfect on this side of the courtyard, and although it is rather cramped, I manage to take photographs of all eight faces of both pillars, and from what I can tell the Tangut text in the photographs is mostly very legible beneath the layer of varnish that has been applied to protect the inscriptions.

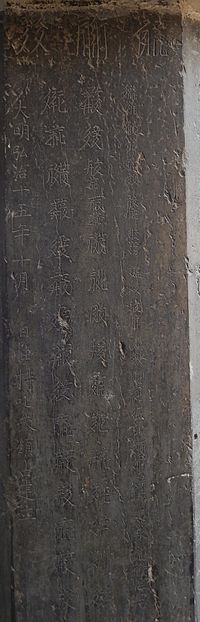

| Detail of one face of one Tangut dharani pillar |

|

| {BabelStone CC BY-SA 3.0} |

| 𘍦𗠁𘞃 |

| The three large Tangut characters at the top (reading right-to-left) *ꞏjij bu̱ dźjow are the title, "Pillar of the Victorious Sign" (Chinese: 相勝幢), referring to the Dharani-Sutra of the Victorious Buddha-Crown. |

| 大明弘治十五年十月 日住持吒失領占建立 |

| Erected by the abbot Trashi Rinchen on a day in the 10th month of the 15th year of the Hongzhi era of the Great Ming |

The Tangut people lived in the area of modern Ningxia and Gansu provinces, more than 500 miles to the west as the crow flies, where they had established the Great Xia State of the White and the Lofty, known to the Chinese as the Western Xia. The Western Xia was annihilated by the Mongols in 1227, after twenty years of war, and the remaining Tanguts who were not massacred by the Mongols migrated westwards or were incorporated into the Mongol Empire. Today the Tangut people and their language have long since vanished. It therefore caused a sensation when these Tangut dharani pillars were discovered in 1962, hundreds of miles away from the Tangut homeland and dating to hundreds of years after the fall of the Western Xia. The pillars are not only engraved with Tangut text, but record the names of more than eighty Tangut people who donated money for their erection, and so are evidence that there was a thriving Tangut community in Baoding during the early 16th century.

Laosuo Stele

Additional evidence of a Tangut community in Baoding is found in the form of the stele standing to the right of the two Tangut dharani pillars (unfortunately not easy to photograph well as it is so tall [3.85 m]). This stele, found in 1985 at Xiezhuang 頡莊, three miles north-west of the Ancient Lotus Pond, commemorates (in Chinese) the life of the Tangut official Laosuo 老索* (1188–1260) and four generations of his family, who lived in Baoding throughout the Yuan dynasty. Laosuo held the post of darughachi (Mongolian: ᠳᠠᠷᠤᠭᠠᠴᠢ; Chinese: 達魯花赤) for Baoding under Zhang Rou, and his family continued to live in Baoding until at least the end of the Yuan dynasty—and probably on through the Ming dynasty.

* Laosuo 老索 is perhaps a transcription of the otherwise unattested Tangut surname 𗒉𗦗 [la so].

| Stele of Laosuo Yuan, Zhizheng 10 (1350) |

| 《大元敕賜故順天路達魯花赤老索神道碑銘》 |

|

|

| {BabelStone CC BY-SA 3.0} |

| Seal script calligraphy on the stele head by Zhang Qiyan 張起礹 (jinshi graduate 1315) |

| Epitaph composed by Ouyang Xuan 歐陽玄 (1283–1357) |

| Epitaph text written by Su Tianjue 蘇天爵 (1294–1352) |

Transcription of the Stele of Laosuo

Front Side

- 大元敕賜故順天路達魯花赤河西老索神道碑銘

- 翰林學士承旨榮祿大夫知制誥兼修國史歐陽玄奉敕撰文

- 集賢侍講學士中奉大夫兼國子祭酒蘇天爵奉敕書丹

- 翰林學士承旨榮祿大夫知制誥兼修國史張起礹奉敕篆額

- 皇帝御極之十年,歲在癸未,制授通奉大夫前河南等處行中書省參知政事訥懷為集賢侍讀學士。越明年春,集賢學士脫憐等

- 言:"訥懷曾大父故順天路達魯花赤老索,當

- 太祖皇帝基命之際,奧有成績,列於功載,宜賜之碑銘,以寵示來裔。其令翰林學士歐陽玄為文,集賢侍講學士蘇天爵書,翰林學

- 士承旨張起礹篆額以賜。"

- 制曰:"可。"臣玄謹按事狀:老索,唐兀氏,世為寧夏人。幼穎悟,長以驍勇聞時。

- 太祖皇帝拓境四方,老索知天意所向,屢諷其國王失都兒忽率諸部降。

- 太祖皇帝素聞其名,及見,偉其材貌,俾入宿衛。老索昕夕唯謹,及遇攻討,被堅執銳,親冒矢石,為士卒先。

- 上益壯之,賜號"八都兒"。八都兒者,華言驍銳無敵也。妻以宮女康里真氏。從征諸部克大水濼,拔烏沙堡,又破桓、撫等州。及分□□□

- 河南武宣王察罕那顏麾下,敗金將完顏九斤、萬奴等軍數十萬於野狐嶺。還定雲內,西徇地至涼州諸郡。

- 太祖皇帝賜金符為統軍,及織紋數十匹,以旌其功。分討欽察、兀羅思、回回等國,推鋒破敵,所向無前。大軍至答也失的□□□號,

- 至險,老索乘勝驅衆涉之,□□平地,斡羅兒、孛哈里、薛迷思干等城皆堅壁,未易猝拔,竟一鼓克之。札剌蘭丁迷里彼驍□□□鐵

- 門閞,老索深入,身中流矢,勇氣彌厲,麾軍力戰,遂平之。

- 太宗皇帝南征,從下河中,定南京。甲午,金亡。詔採良家女以備後宮,諫曰:"中原甫定,宜收攬英雄,以開混一之業,今乃嬪……"

Right Side

- 大□賜曰 全□兩丙申(使?)□□…… 盛順天□汝南忠武王張公□□□老索協力屏翰(請?)□□□(六?)□□於……碑

- 燕南自為一路,民至今便之。(年?)一十即上惠(符?)乞□骨……

- 上優憐之,賜黃金五十兩,白金三百兩。中統建元六月二十三日薨於正寢,壽七十三。越明年某月日,葬於清苑縣太靜鄉之先塋。

- 康里追封夫人。子二人,長阿(勾)早亡。次忙古,起家為行軍千戶。丁巳,攻蜀,所至先登。己未,

- 憲宗圖合州釣魚山,克捷居多,□□常勝,遂沒於陣,贈至中大夫,僉太常禮儀院事。娶眭氏,子一人,忽都不花,德器溫厚,至元十七年,

- 擢奉議大夫、祁州達魯花赤。為政明恕,編氓以其有德,至今以顏子目之。秩滿

- 光獻翼聖皇后以其

- 先朝舊臣,諭都官不次擢用。時阿合馬柄政,官非賂莫進,忙古疑為忽都不花之誤。慨然曰:"為民父母,罄產鬻官,而復刻削於民以求利,可乎?"遂無仕進

- 意,移遂州達魯花赤。至元二十一年五月九日,卒於家,年三十有六。娶民氏,奉柩歸葬於清苑之先塋。子一人,即訥懷,父沒年甫三

- 歲,母民氏□□守義,育鞠有加。既長,從師問學,涉獵經史。入京,因司徒明里以見

- 仁宗皇帝於□□□□(使?)左□□授中書直省舍人沿榭護送趙王公□□,道塗禁戢其徒御,所過郡邑無擾,歸以能聲,

- 廟堂遷知安東□選□監察御使□□□曰:"汝父連收二州,雖獲廉而未嘗預清要之選,汝今得之宜效節以報國顯親□……"

- 尋拜河東廉訪使□□宣□,有世襲,知府怙寵不法,輒發其奸,獄成而逃,訴於朝

- 由……是

Left Side

- □□□□□登佚氏生□□鄙……葬於□□□南大同,魂無不之……

- □子有孫□□□忠順匯此慶澤,發於曾孫,曾孫勉……遭文

- □皇□□□謹(定?)令譽進登察(官?) 踐揚中朝……參預兩省……子

- 我皇□淵□寔□□輕……進(照?)生功顯爾,引下曾孫,有母實賢,秉節迪人,式隆其傳。

- □二業□□□□未表其進□□□□□自我(基?)命,(貞?)有諡,及告奉常,詞□臣……□苑之南賁爾貞域……之

- 銘……

- 聖世之德

- 至正十年四月吉日曾孫訥懷立石

- 保定儒士李肅、處士胡賓元摹

- □(玉)川、蔣伯從、劉弘毅、張寬刻

Translation

[I have published a revised translation and notes on my BabelStone blog under the title Two Tangut Families Part 1 : Laosuo]

Front Side

Spirit-Way Stele Inscription of Laosuo of Hexi, the late Darughachi of Shuntian Route, bestowed by imperial command of the Great Yuan.[1]

Text composed by imperial command by the Hanlin Academician Recipient of Edicts, Grand Master for Glorious Happiness and Drafter, concurrently Compiler of the Dynastic History, Ouyang Xuan (1283–1357).

Written down in red ink by imperial command by the Worthy Attendant, Expositor and Grand Master for Palace Attendance, concurrently Libationer of the National Academy, Su Tianjue (1294–1352).

Seal script heading written by imperial command by the Hanlin Academician Recipient of Edicts, Grand Master for Glorious Happiness and Drafter, concurrently Compiler of the Dynastic History, Zhang Qiyan.[2]

In the 10th year after the accession of the Emperor [Shundi] (r. 1333–1370), in the cyclic year guiwei (Year of the Water Goat) [1343], Noqai, Grand Master for Thorough Service and previously Assistant Grand Councilor of the Branch Secretariat of Henan etc., was made a Worthy Attendant and Academician Reader.[3] In the spring of the following year the Worthy Academician Tuolian and others said: "The great grandfather of Noqai was Laosuo, the late Darughachi of Shuntian Route. At the time that Emperor Taizu [Genghis Khan] (r. 1206–1227) was establishing his mandate he had great achievements and was listed on the roll of honour. It is fitting to bestow a memorial inscription on him, in order to show favour to his descendants. It should be commanded that the Hanlin Academician Ouyang Xuan compose the text, the Worthy Attendant and Expositor Su Tianjue write it down, and the Hanlin Academician Recipient of Edicts Zhang Qiyan write the seal script heading. [The emperor's] edict said: "Permitted." I, [Ouyang] Xuan, carefully note the facts of his life:

Laosuo was a Tangut, and his family had lived in Ningxia for generations.[4] When he was young he was intelligent, and when he grew up he was renowned for his courage. When Emperor Taizu was expanding his territory in all directions, Laosuo knew which side Heaven favoured, and several times admonished his king, Shidurghu (r. 1226–1227), to lead his forces in surrender [to Genghis Khan].[5] Emperor Taizu had long heard of his name, and when he saw him he thought that he had an impressive demeanour, and so had him join his bodyguard. Laosuo diligently [carried out his duties] from dawn to dusk. When it came to fighting the enemy he wore sturdy armour and carried a sharp blade, dodging arrows and missiles he led the troops from the front. The emperor considered him to be even stronger, and gave him the name Ba'atur, which in Chinese means "brave and indefeatable".[6] He gave a palace girl of the Zhen family of the Kankalis tribe to be his wife. He participated in campaigns against the various tribes, and [was in the army that] defeated the enemy at Big Water Lake and Bawusha Fort; they also captured Huanzhou, Fuzhou, and other places. He was put under the command of Chaqan Nayan,[7] Prince Wuxuan of Henan, and they defeated an army of several hundred thousand commanded by the Jin generals Wanyan Jiujin and Wannu at Wild Fox Peak. On their way back they pacified the region of Yunnei, and went westwards as far as Liangzhou. Emperor Taizu gave him the gold tally of an army commander, as well as several tens of bolts of cloth, in order to celebrate his success. He separately participated in campaigns against the countries of the Kypchaks, Russians and Persians. He charged into the enemy and no-one was ahead of him in battle. When the main army arrived at Dayeshi ... in great danger, Laosuo followed up the victory by chasing after them ... level ground. The cities of Woluo'er, Bukhara and Samarkand all had strong walls, and it should not have been easy to take them quickly, but unexpectedly they were captured with a single roll of the drums. ... the iron gates closed, and Laosuo went deep in. He was hit by a stray arrow, but his bravery was undiminished, and he led the army in battle, thereupon defeating [the enemy]. When Emperor Taizong went on a campaign to the south he accompanied him into the Hezhong region and pacified the Southern Capital. In the cyclic year jiawu (Year of the Wooden Horse) [1234] the Jin state was overthrown, and [the emperor] ordered girls from good families to be selected for the inner palace. [Laosuo] remonstrated, saying: "The Central Plains have only just been pacified, so it is fitting to gather together heroes in order to establish an empire, but now it is concubines ..."

Right Side

[Emperor Taizu?] bestowed ... ounces of gold. In the cyclic year bingshen (Year of the Fire Monkey) [1236] ... Shuntian ... Prince Zhongwu of Runan, Lord Zhang,[8] ... Laosuo's assistance was a great help ... at ... stele. Yannan was created a Route in its own right, which the people up to now consider to be a beneficial. ... The emperor loved him dearly him, and bestowed upon him fifty ounces of gold and 300 ounces of silver. On the 23rd day of the 6th month of the 1st year of the Zhongtong era [1st August 1260] he died in his sleep. His age was seventy-three. On a certain day and month of the following year he was buried in the ancestral burial ground at Taijing District in Qingyuan County.[9] His Kankalis [wife] was retrospectively created a Lady. He had two sons, the eldest, Agou (?), who died young, and the second, Manggu, who left home to become a Battalion Commander in the army.[10] In the cyclic year dingsi (Fire Snake) [1257] he attacked the region of Shu, and wherever he went he was always first into battle. In the cyclic year jiwei (Earth Goat) [1259] Emperor Xianzong (r. 1251-1259) tried to take Fishing Hill in Hezhou, and he had many victories ... was often victorious, but then he fell in battle. He was posthumously promoted to the position of Grand Master of the Palace serving in the Commission for Ritual Observances. He had married a lady of the Sui family, and had one son, Qutu-buqa, who was virtuous and amicable.[11] In the 17th year of the Zhiyuan era [1280] he was given the position of Grand Master for Palace Counsel and Darughachi of Qizhou. In government he was enlightened and forgiving, and the registered populace thought he was virtuous. Up to today he is looked upon like [Confucius's disciple] Yan Hui. When his term of appointment was over, on account of his being an old minister at the previous court, Grand Empress Guangxian Yisheng (c. 1161–1230) told the Ministry of General Administraion to give him an extraordinary appointment.[12] At that time Ahmad Fanākatī (d. 1282) was in power, and an official did not gain promotion without bribery. Manggu throught that [his son's lack of promotion] was Qutu-buqa's own fault.[13] [Qutu-buqa] impassionately exclaimed: "Is it right for an official, as the parent of the people, to empty the coffers to buy an appointment, and furthermore to harshly treat the people in order to seek profit?" Thereafter he had no desire to progress in his official career. He moved to be Darughachi of Suizhou. On the 9th day of the 5th month of the 21st year of the Zhiyuan era [25th May 1284] he died at home. His age was thiry-six. He had married a lady of the Min family, and she took his coffin back to be buried in the ancestral burial ground in Qingyuan. He had one son, namely Noqai, who was just three years old when his father died. His mother, Madam Min ... remained a widow, living in increasingly straitened circumstances as she got older. When [Noqai] grew up, he studied under a teacher, and read a little of the Classics and Histories. He went to the capital, and through the minister Mingli[14] he was able to have an audience with Emperor Renzong (r. 1311–1320) at ... left ... conferred on Yan Xie, Drafter of the Secretariat of the Metropolitan Area, the task of escorting Prince[ss] Zhao ... On the road carriage-bearers and riders were prohibited, and there were no disturbances at any of the places they went through.[15] On his return he gained a reputation for being capable. At the imperial court he was promoted to Andong ..., selected ... Investigating Censor ... said: "Your father captured two cities in succession, and although he had a reputation for being honest (?) he never put himself forward for selection for a sinecure. Now that you have received one, it is appropriate that you do your utmost to repay your country in order to bring honour to your parents ..." ... went to pay his respects to the Investigation Commissioner of Hedong ... hereditary, the Prefect relied on the emperor's favours to break the law, and his treachery was often exposed, but he escaped prison and appealed to the court ...[16]

Left Side

[7 lines of a fragmentary poetic eulogy not translated.]

Memorial stone erected by [Laosuo's] great grandson, Noqai, on an auspicious day of the 4th month of the 10th year of the Zhizheng era [7th May to 4th June 1350].

Text copied [in preparation for engraving] by the scholar Li Su and the recluse Hu Binyuan from Baoding.

Text engraved by Jiang Bocong, Liu Hongyi and Zhang Kuan from Yuchuan (?).

Notes

- A Spirit-Way Stele Inscription is an epitaph inscribed on a stele that is erected at the site of someone's grave. This stele was presumably erected by Laosuo's grave.

- Zhang Qiyan was a painter and calligrapher (his dates of birth and death are unknown, but he was a jinshi graduate of 1315). His name is written as 張起礹 on the inscription, but is normally written as 張起嚴 in other Yuan dynasty sources.

- Noqai ᠨᠣᠬᠠᠢ (transcribed in Chinese as nèhuái 訥懷) is a Mongolian name meaning "Dog".

- Under the Mongol scheme for classifying nationalities, you did not need to be an ethnic Tangut to be classified as Tangut, but only had to come from the region occupied by the Western Xia state. From Laosuo's name it is evident that he was not only classified as a Tangut but was indeed an ethnic Tangut.

- Shidurghu ᠱᠢᠳᠤᠷᠭᠤ (transcribed in Chinese as shīdū'érhū 失都兒忽) was the name given to the last emperor of the Western Xia by the Mongols, and is a Mongolian word meaning "simple, right, just". In François Pétis de la Croix's 1710 Histoire du Grand Genghizcan (translated into English in 1722 as The History of Genghizcan the Great), which was based on Turkish sources, his name is given as Schidascou.

- Ba'atur ᠪᠠᠭᠠᠲᠤᠷ (transcribed in Chinese as bādū'ér 八都兒) is a Mongolian word meaning "hero" or "brave, courageous".

- Chaqan Nayan was a Tangut general who fought under Ghengis Khan.

- Prince Zhongwu of Runan is Zhang Rou 張柔 (1190–1268), military governor of Baoding, who rebuilt the city after it had been devestated during the war against the Jin.

- Qingyuan County 清苑縣 was the county covering Baoding city.

- Manggu (transcribed in Chinese as mánggǔ 忙古) is a Turkic name meaning "Eternal".

- Qutu-buqa ᠬᠤᠲᠤ ᠪᠦᠺᠠ (transcribed in Chinese as hūdū bùhuā 忽都不花) is a Mongolian name. The first element corresponds to Mongolian ᠬᠤᠲᠤᠭ qutuɣ, meaning "blessing, bliss, benediction, happiness". The second element corresponds to Mongolian ᠪᠦᠺᠠ buka, meaning "ox, bull".

- The sentence starting "When his term of appointment ..." can only refer to Laosuo, as the Grand Empress Guangxian Yisheng (wife of Genghis Khan) died in about 1230, but in that case the sentence is out of place.

- This sentence makes no sense to me, as Manggu apparently died in battle in 1259, when his son was only about ten years old.

- Mingli is perhaps Mingli Donga 明里董阿 (d. 1340), who was the head of the Bureau of Imperial Manufacture (see James C. Y. Watt, When Silk was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997) p. 96). "Minister" (Chinese Situ 司徒) is here a courtesy title rather than the title of an actual position. His name is Turkic, meaning "Tiger with a birthmark" (mäŋlig toŋa).

- It is not clear to me what role Yan Xie has in the mission to escort Princess Zhao on her journey, as it seems to be Noqai who gets the credit for a job well done. Nor do I understand the statement that "On the road carriage-bearers and riders were prohibited".

- I do not know who the last sentence on the right side of the stele is talking about, and how this relates to Noqai.

The Stele of Laosuo indicates that some Tangut people settled in the Chinese heartland as officials under the Mongol regime or as soldiers in the Mongol army. The two Tangut dharani pillars suggest that religion was another impetus for Tangut migration. The Mongols were patrons of Tibetan Buddhism, and under the Yuan dynasty Tibetan lama temples were established in Beijing and elsewhere in northern China. The Tanguts were proponents of Tibetan esoteric Buddhism, and it seems that Tangut Buddhist monks often populated the Tibetan temples set up by the Mongols—perhaps it was easier to get hold of Tangut monks than it was to get monks to come all the way from Tibet. The Cloud Platform at Juyong Pass was originally set within the Yongming Baoxiang Temple (永明寶相寺), which was established by imperial command during the early 14th century, and the fact that Tangut was one of the scripts used to engrave dharani inscriptions there suggests that Tangut monks would have been resident in the temple.

The distinctive feature of the Temple for Promoting Goodness (Xingshan Temple 興善寺) in Baoding, where the Tangut dharani pillars were found, was a white stupa-shaped Tibetan-style pagoda, of the type found at the Miaoying Temple in Beijing. This pagoda, as well as the Tibetan name of the temple's abbot, clearly indicates that the temple was a Tibetan lama temple; and it was almost certainly established in the early 13th century when Zhang Rou was rebuilding the city. This temple, with its contingent of Tangut monks, would no doubt have been the focus of life for the Tangut community in Baoding. Sadly, the temple fell into disrepair during the Qing dynasty, and it seems that in 1900, in the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion, the temple was burnt to the ground by the forces of the Eight Nation Alliance. One can only wonder what Tangut scriptures may still have been stored in the temple library when it was put to the torch.

Other Sculptures

Time is getting on, and before we leave for this afternoon's excursion we take a brief tour around the gardens.

Headless sculpture of an official

Turtle stele bases

Stone animal sculptures

Postscript

On my trip to China in September–October 2017 I stayed in Beijing for two before going to Inner Mongolia, and on the second day I went by train to Baoding to revisit and rephotograph the Tangut dharani pillars, as documented in this post.

Hebei | Ming dynasty | Tangut

Index of Rambling Antiquarian Blog Posts

Rambling Antiquarian on Google Maps